Simon Edwards: The exhibition you are preparing for the Salon de la Photo focuses on the image of women in your work. When did you start to emphasise the everyday life of women? Was it conscious or unconscious?

Françoise Huguier: It was a bit unconscious. I have always photographed women more than men. First of all because in the houses or in the markets it was often the women who were there. Like in the communal flats in St Petersburg. There were a lot of them, they lived alone and that was what interested me.

S.E.: At the beginning of your career, you started reporting for yourself, you went to Indonesia and lived in traditional communities that have not changed for thousands of years. How did you approach this reporting?

F.H.: At the beginning I worked for a newspaper called 100 Idées, which had an extraordinary art director. There were 15-page stories with texts on curiosities. When I went to Indonesia, I proposed a subject on leather lace puppets for ceremonies in Bali and then I did the history of bamboo, the history of tea and that's how I started. The last subject I did for them was school uniforms in Japan and I realised that I was starting to be more interested in the social than the curios. It was at that time that I met Christian Cajole, who offered me to work for Libération and I said yes. I was commissioned to write about cinema and especially society. Like, for example, the woman who lived in the basement of a council flat in Poissy in the 1980s. One day I said that I would like to follow Mitterrand's trip to West Africa. I was fascinated by it, because it's not my kind of photography. There were two other photographers with me. I have an anecdote about this. It was during a little lunch with Chirac, who was prime minister at the time, Mitterrand and Idriss Deby. We were around the table and the two other photographers, whose names I won't mention because I like them a lot, were pushing me around. I remember that François Mitterrand said to them, "Let Françoise do her job a bit". Mitterrand was an extraordinary person, who, when he saw you once, remembered your name.

S.E.:Did you feel apprehensive or afraid when you started reporting? When I read your book Au doigt et à l'œil, I have the impression that you were frank about it.

F.H.: I didn't go to photography school and at the beginning when I started, my father said to me "I don't understand why you're doing this, photography is good for the family albums". My father was an engineer, so he was far from all that. My mother understood. One day she attended a fashion shoot I did in Brittany. When you do fashion photography, you are a director. My mother said to me: "Now I understand why you do photography, it's because you order...". At the beginning, when I was walking down the street with my camera on my stomach, as soon as I entered a bistro, everyone looked at me and it made me feel very uncomfortable. I had a lot of trouble at the beginning, but now, when it comes to photography, nothing scares me anymore.

S.E.: The end of the sixties in Paris was a very eventful and formative period for a young photographer in the making. It was the time of Saint-Germain-des-Prés and its Drugstore for example, where you could find everything. Did this period inspire you a lot?

F.H.: Yes, very much so. Saint-Germain was very interesting at the time. In the Drugstore there were a lot of photos on display. Now it's gone, it doesn't exist any more because there's a fashion shop in its place. My parents lived in the area and I was a student at the time. I was for freedom. I don't want to bother people with freedom, but for me it's very very important. I hope it will continue. Freedom of thought, freedom to do things but to do them with class and with respect. I learned respect from my parents and also in Africa, where it is very important. But in my head I am free and that's what I like. I pay a lot of attention to who I'm dealing with and often my friends tell me that I have eyes like scanners. It's true, I can see everything, but I've learnt that little by little. It's because I have this sense of freedom. I'm like a cat, I prowl around people until I find the right moment. I ask questions, and then all of a sudden... paff !

S.E.: Can you tell us about your experience with Secret Africa, the long report on these discreet women in Burkina Faso and Mali?

F.H.: How did I get to Mali? Until then I had been going mainly to Asia, to Japan and Korea. One day an anthropologist friend, Jean-Jacques Mandel, said to me "Françoise, you should go to Mali". So I took a house on the banks of the Niger in Ségou where my friends came to tell me their stories. They came to confide in me. They often spoke to me about excision and polygamy. I started taking photos in this house, then in the neighbourhood and finally in the women's room. In Mali the women's room is very important. It is where they keep all their secrets. Men, I say in my book, are like bumblebees. A man who has two wives spends two days with one woman and two days with another, he has no room. That's how it is in polygamy. In the women's room the stepchildren are not allowed in, nor the mother-in-law, because the woman has all her secrets there. They don't tell their secrets to their husbands, of course, or to their children, but rather to their daughters than to their sons, and that's why I called them Secret.

S.E.: These women came to see you and you befriended them, so you were able to photograph them afterwards.

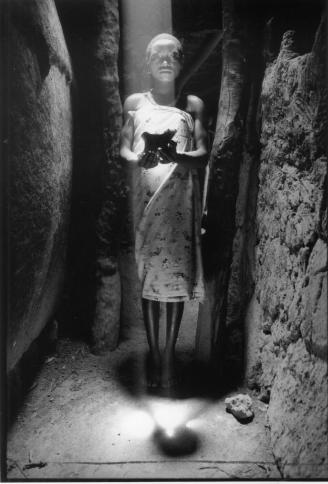

F.H.: In Ségou they accepted and then I went to Côte d'Ivoire and Burkina Faso to photograph the women's room. I left Abidjan and arrived in Burkina at the Lobis on the border with Ghana. Then I went back to Mali via Ouagadougou and then Mali, to the Dogon country. I took a lot of photos in these Lobi villages in Burkina. The houses are like little earthen castles, the women build them and decorate the outside. Inside it is very beautiful, because it is both their home and their attic. There are holes of light coming from the terrace, as if the Holy Spirit was lighting them. I took a photo of a girl in a loincloth under this light, like an Egyptian goddess. It was very important for me to do all this work. If I hadn't talked a lot beforehand with my friends in Mali I would never have had the idea of doing the women's rooms.

In 1988-89, I undertook a crossing of Africa from Dakar to Djibouti which became a book, L'Afrique Fantôme, in the footsteps of Michel Leiris, and I fell in love with Mali. I go there every year, and that's how I followed bands, including the Super Bitton, and became passionate about Malian music and the Mandingo empire. The Mandé Charter (12th-13th centuries) is the charter of human rights that dates from long before ours. The Mandingo Empire was a very important empire, which unfortunately is not taught in French schools, but in Mali and Guinea. There is the "joking cousinhood" between ethnic groups, which dates from the same period.

S.E.: Your work on KPop is delirious and very colourful. Did young Malaysian women and boys play this game very easily? Later in Seoul you explore the place of women in society. Can you tell us about this?

F.H.: I had been to South East Asia a lot in the 75s and 80s and I wanted to go back and see the emergence of the middle class due to economic success. When I got the prize from the Academy of Fine Arts, I went back to Singapore, Kuala Lumpur and Bangkok. I exhibited this work in Paris and then in South Asia. When I returned to Kuala Lumpur, my friend, Ponk, who is now a photographer, said to me "there is a Korean KPop singer who is giving a concert". I asked him, "What's that? He said "you'll see". I went there, it was amazing. The singer's name was G-Dragon, he was an amazing performer. My friend told me that there was a shopping mall for KPop fans and we visited it. I then wanted to do portraits, on backgrounds in Chinese owned Malls, who gave me permission. We put an advert on Facebook for the casting and the young people came all dressed up and made up.

S.E.: How do you see this fashion? What do you think makes these young girls and boys dress in such an extravagant way?

F.H.: It comes from Japan. There is a place in Tokyo where every weekend people meet. In my time it was more rockabillies, now it's more Harajuku1. In Japan they go even further, because there are people who live like their character, always dressed the same, even at home.

S.E.: It's like this phenomenon in Japan of young people who lock themselves in their rooms and don't want to go out anymore.

F.H.: Exactly. But in Korea, where society is very strict, for young people it's a way of pushing the limits. The first Kpop band was first produced by three jazz musicians. Now it's a very successful business, you can't meet them anymore. It took me a month to get permission to photograph the group "La Boum". I organised everything, rented a studio, and did a "tea at Marie-Antoinette" set, inspired by the Sofia Coppola film. Then I found the stylist for the dresses. The girls were fourteen years old, their faces completely retouched. In Korea, when you pass your high school diploma, your parents pay for plastic surgery. It's an old tradition. Even before that time, when there was only make-up, if you wanted to get married and have a job, you had to have a good physique. Before I left, I met Valérie Gelézeau, director of studies at the EHESS and a specialist in Korea who has worked on appearance and aesthetics. Now in Seoul, there are whole avenues of aesthetic clinics.

S.E.: For 30 years you have been walking around the workshops and fashion shows. Reading your autobiographical book, one gets the impression that you had to struggle at first to be able to produce intimate fashion photography that reveals beauty and creativity. How did your work, which you call "Sublimes", develop in those years?

F.H.: I started at Libération when the paper opened up to fashion. So I was already on the catwalk, but getting into the workshops was another matter, everything was closed. And there weren't many women photographers around the catwalk. I didn't want to be at the end of the catwalk because all the photographers were already there three hours before. As a woman I was told "please stand behind". I heard everything, it was really a war. It was also very difficult to get backstage, so my photos had to be published first. I started with Christian Lacroix who was with Patou. With him it was easier because he was at the beginning and I followed him to the end. It's a fascinating world. I discovered the haute couture workshops where there are no sewing machines, everything is handmade. It's French know-how and it's unique in the world. At that time I photographed all the star models, even Carla Bruni. And I even dared to cut their heads off.

S.E.: It was precisely the formation of your style, the elements of the dresses, the movements and the parts of the body,

F.H.: It's true that I liked to photograph models from the back, a piece of dress, a shoe, a light on a fabric...

S.E.: I think that this kind of photography has greatly influenced the photographers who came after you, because when we leaf through fashion magazines we don't see the whole, we only see parts of the clothes. You have left a mark I think in the approach to fashion photography. Your interpretation of the veil in the series Hijab in South East Asia shows a new way of expressing yourself as a woman despite the demands of religion. How did you approach this subject?

F.H.: I did a workshop in Jakarta where there was a girl wearing a very colourful hijab, whereas here it is often white, beige or black. I wanted to do a series on this theme, but I was leaving for Bandung. This girl explained to me that she had a bunch of friends in Bandung that I could contact. I went to a shopping mall where you can buy everything, wedding dresses and so on, and I could do a series with them. I was very excited about it. It's also a fashion, very colourful, and a continuation of the work I did in France. There are Indonesian designers who are quite well known for their hijabs, wedding dresses and embroidery, it's a real fashion statement. In the shopping mall, I photographed a young woman in a hijab, dressed as Hello Kitty. They were very amused that I did this.

S.E.: We don't feel what we've been experiencing in Europe and in France for the last few years in relation to this.

F.H.: For me, everyone does what they want as long as they don't kill.

S.E.: When you travelled to Colombia, your focus was on the lives of nuns in convents. From very diverse ethnic backgrounds, how do these women see the world today, if it concerns them at all? How were you able to gain trust with these women who have withdrawn from the world?

F.H.: I had already exhibited in Colombia, especially the community flats, and I wanted to go back there to take photos of the nuns. I was inspired by my grandmother's missal with pious images. A cultural attaché friend of mine introduced me to the director of a Jesuit university. Thanks to him I was able to enter the convents. The Ursulines, but also convents whose congregation I didn't even know. Then I went to Cali to a convent of Carmelites, who are recluses, and to the community of the Clarists, where the nuns spoke only to Jesus Christ and their confessor. Only the headmistress had the right to speak to me. I myself was brought up by nuns. At the MEP I exhibited these photos as if in a chapel with a prie-Dieu and also in Gap in a hotel called... Le Couvent!

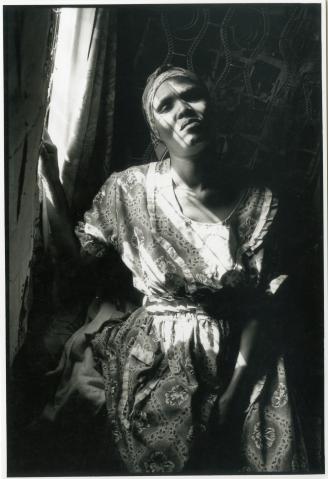

S.E.: During your many trips to Russia you started a work called "Kommunalka". It's a story about the inhabitants of the communal flats in Saint Petersburg, Russia, and it spans 15 years. What prompted you to undertake this work, whose images of women are of astonishing and dark beauty?

F.H.: In these flats there are also doctors, writers and philosophers. These communal flats date from the construction of the Soviet Union, because there wasn't enough money to build buildings like you see in the suburbs today. In Lenin's time, and afterwards in Stalin's time, which was even worse, we would go to rich people who had flats of 200 square metres and more and say to them, "You have a big flat that you own. You can keep two rooms and we will put workers from the countryside in the other rooms". That's how it started, with the kitchen and the bathroom in common. Before leaving for polar Siberia (En route to Behring) I met an ethnologist, a specialist in shamanism, who lived in Saint Petersburg. My interpreter and I looked for her and she lived in a communal flat. It was thanks to her that I got to know these dwellings. After my trip to polar Siberia, I decided that I really wanted to do a work on this subject. I went first to a first, then a second and then a third flat. There was a lady painter with whom I rented a room just opposite the Hermitage Museum who had a friend in a communal flat, so, thanks to her, I was able to move from room to room. I worked in Saint Petersburg on this subject for two or three months a year for ten years, and I also made a documentary on one of these flats, which was shown in Cannes and in movie theatres in Paris.

S.E.: In the photographs in the exhibition we see images of women of extraordinary sensuality and also, as you say, images inspired by the Russian film-maker Andrei Tarkovsky with his colours, his suggested, mysterious and anguished atmospheres. There is no judgment or critical look in these images. We see the women as they are, naked or dressed.

F.H.: When I came back from my trip and was talking to my interpreter, I explained to him that I wanted to photograph nudes. He told me that I was "crazy. It's impossible to do that! For me, "impossible is not French". In the flats, he told everyone "Françoise wants to do nudes". The answer was yes, because women wanted to pose for an artist. This is a country where they still accept, whereas it has become very difficult here in France. In the photo "The Nude with Newspapers" the girl was repainting her flat, she had put newspapers to protect the floor. I started to photograph her in her panties, and then I said to her, "Don't you mind putting your back to me, naked? That's how I started. It was a very gentle process. I am the age I am and I am a woman.

Working for Greater Paris, I went to 35 families around Paris. But I don't arrive at their homes and say "let's take some photos". I tell them my life, my seven different lives (laughs). I look around at everything, on the walls, on the ceiling and on the floor, while we have coffee, and then I ask if I can go to the toilet. Why do you ask? Because in the toilet there are always newspapers, pictures, toilet paper and the kettle for washing in the Muslims. I come out of the toilet and say "oh, the little boy in the picture, who is he?" and they say "well, he's my grandson, do you want to see his room? Then I was shown around the flat. When I got to the grandmother's room, I said, "Can I see your wardrobe?" When I took out a piece of clothing I exclaimed "Ah, it's so beautiful, don't you want to wear it? And in the shower, I've sometimes succeeded too.

S.E.: You are a real film director. Let's talk about tattooed women, you've done quite a few too. That was in Japan.

F.H.: It was thanks to Issey Miyake, in 85 or 86. I knew that there was a great tradition of tattooing in Japan. Issey Miyake introduced me to the master tattooist Horiyoshi III (who has now passed away) and I spent a week with him. The tattoo artist hosted artisans and Yakuza. I photographed him working. There was even a man who had his sex tattooed, whom I asked to get naked, he accepted. I photographed everything that inspired this master, like his collection of old Japanese prints. In Singapore, while photographing the families in the HDBs (public housing), I met a couple of tattooed architects, I couldn't resist. In Bangkok, there are many tattoo studios. Gatai, my interpreter, told me: "Let's go to the big market, there are many tattooed men and women. And at a flower shop she knew, she had a surprise in store for me: the owner was completely covered in traditional Buddhist tattoos, with dildos on his belt. Gatai then took me to a rockabilly band's frontwoman, who had a beautiful panther tattooed on her back.

S.E.: What are your current projects?

F.H.: The photographic chronicle of the physiotherapist's office where I have my capsulitis treated. And a report on the Herrenknecht factory in Germany, which manufactures tunnel boring machines for the whole world, including for the Grand Paris Express metro.

1 The Harajuku style takes its name from the Harajuku district in Tokyo. In the beginning, local youths occupied the streets wearing unique and colourful outfits. The first craze was to mix traditional Japanese clothes with western clothes. The message these young people were sending was that they didn't care about mainstream fashion. They wanted to dress the way they wanted to.

Discover the genesis of the exhibition "From Woman to Women".